Debates over “civility” are nothing new for Quakers. And other people.

The last time I was thrown out of a retail establishment, it was a screen printing shop in Fayetteville NC, near Fort Bragg. I came in on a warm day in 2007, wanting some tee shirts made for a conference being planned by Quaker House. The shirts were to be black, and the wording something like this:

I handed over a CD with the image on it, and the guy at the desk put down his cigarette & slid it into a computer. I couldn’t see the screen when the image came up; but his widened eyes told me.

He stood up as the CD slid back out of the slot. “Hey, Sarge,” he called, and carried it into a back room.

“Sarge” was out in a couple moments; likely retired Army. He didn’t throw the CD at me, but dropped it on the counter and made clear in a loud voice that anybody at Guantanamo or what we were just learning to call “black sites” was a goddam terrorist who deserved whatever they got, and that he was not about to print such treason as this on any of his shirts.

I didn’t quibble. But I called the next shop on my list before I went in, to see if they too had any objection. The shirts got done. And I didn’t think til later about how the issue of who was being uncivil here could be fitted into the “It’s Complicated” category:

Was it “Sarge,” who at best might have considered my image some very bad joke that didn’t play; or was it I, who brought such a patently offensive message into his patriotic establishment?

Or consider this image:

It’s a satire on the refusal of early Friends in England to pay “hat honour” or bow to their social superiors. Mention of this “witness” does not produce much of a reaction today. But many early Friends paid dearly for such effrontery

Meantime, across the pond in Massachusetts Bay colony, the “Puritan Fathers,” who never meant to establish any religious liberty (except theirs), decreed that fines be levied against persons who did NOT attend their official Sunday church services.

Among those who defied this law was a local Quaker convert named Lydia Wardell and her husband Eliakim. The authorities stripped their home and farm of almost all property of any value to pay the succession of fines,  and repeatedly summoned Lydia to appear at the church service to account for her absences.

and repeatedly summoned Lydia to appear at the church service to account for her absences.

This she did in May, 1663, but when she came into the church she was naked, thereby, says one historian, to stand as a “sign” of the authorities’ “spiritual nakedness.”

For which incivility she was arrested, tied to a whipping post, stripped to the waist and given 20 to 30 stripes.

Civility, incivility and violence; they’re often closely related. Soon Lydia and Eliakim moved to New Jersey.

A few years later, the palace elite in London was aghast when King Charles II agreed to meet with the rising Quaker leader William Penn.

This painting does not convey the courtiers’ consternation and indignation at the upstart Quaker, though the main cause is evident in that Penn, wearing the unadorned gray coat, is also the only one with his hat on. Any other commoner could end up in the Tower for that.

Yet Charles, perhaps having a sense of the ridiculousness of such customs, also had a not-so-hidden reason for tolerating what to the others was open insolence: Charles had been a refugee for a decade after his father, Charles I lost the English Revolution, his throne, and his head, and the monarchy was abolished. In his years on the run, Charles had borrowed a lot of money from Penn’s father, a wealthy admiral and landowner.

Charles regained the throne in 1660, and when the elder Penn died, the younger inherited the debt — which Charles would much rather not pay, preferring to spend money on luxuries and mistresses.

So Charles tried the art of the deal: ignoring the black hat, he offered to “pay” Penn with a big swath of land on the east coast of what was called the “New World.” Charles hoped Penn would not only accept, but also persuade his peculiar and often troublesome fellow Quakers to settle there with him. Then they could practice all their weird religious and social ideas, across the Atlantic, far far away from the (momentarily) debt-free Charles.

It would be, if the king had known modern lingo, a “win-win.”

As some of us recall, Penn went for the deal, but we’ll skip the rest of his story, which didn’t go all that swimmingly — except to mention that future breaches of “civility” would play a role in various emerging issues.

In this Philadelphia history, there are some figures who are renowned for their “civility,” and perhaps none more so than John Woolman. He worked patiently and seemingly always inoffensively, to persuade other Philadelphia Quakers that slavery was an evil of which they should free themselves; a labor which was eventually crowned with success. If Quakers were to have a patron saint of civility, he would be the one. Some today place him beyond mere sanctity: he’s more like the very archetype and gold standard of Quaker authenticity.

In this Philadelphia history, there are some figures who are renowned for their “civility,” and perhaps none more so than John Woolman. He worked patiently and seemingly always inoffensively, to persuade other Philadelphia Quakers that slavery was an evil of which they should free themselves; a labor which was eventually crowned with success. If Quakers were to have a patron saint of civility, he would be the one. Some today place him beyond mere sanctity: he’s more like the very archetype and gold standard of Quaker authenticity.

A famous historian wrote later that “Close your ears to John Woolman one century, and you will get John Brown the next, with Grant to follow.” That is well-put, but too neat. Before John Brown you got other, different Quakers, aiming to head him off. Times changed in the decades after Woolman’s death in 1772. His quiet crusade was for manumission, where owners voluntarily freed their chattels; even with all his modesty, it ran into plenty of opposition. But sixty years later, that was not enough, and a new cry was heard, for abolition: that slavery be made illegal, the whip snatched from the masters’ hands, and all those held in bondage be freed, immediately.

Just hearing that proposition, be it ever so delicately phrased, sent many slavery supporters into paroxysms of insulted rage. Such incivility was not to be tolerated: in most of the South it was soon made into a felony, and the U. S. mails were searched and cleansed of “incendiary” publications.

Quakers were among the first to speak for abolition. They did so over the stiff objections of a Quaker establishment, many of whom were people of wealth, and all of those who were in commerce were also deeply entangled with the slave economy.

“Yes, slavery is evil,” the establishment said. “But the ending of it is in God’s hands, not ours. So steer clear of it, pray for its end, and keep quiet.”

There was soon resistance to this edict, and some of the most forceful came from Quaker women. Among abolition’s earliest public advocates were two sisters, Angelina and Sarah Grimke, Quaker converts raised in a wealthy slave-owning South Carolina family. They left the South for Philadelphia, and what they thought was a supportive base for their religious and social reform impulses.

It turned out they were mistaken. The Quaker establishment accepted them as members, but then wanted them also to keep quiet: their firsthand stories of southern slavery were bound to stir up trouble. Incivility again.

But the sisters didn’t, couldn’t comply; and Angelina proved to be a remarkably articulate and persuasive speaker. In late 1837 they were invited to make a speaking tour of Massachusetts, where they drew huge crowds day after day, speaking of slavery and abolition. But here they also ran smack into vehement charges of more scandalous incivility.

Their worst offense was not speaking against slavery, but speaking at all. Or rather, doing so before promiscuous audiences; that is, groups including both women — and men. Together!

Members of a prominent association of Massachusetts Congregational ministers were so shocked at this shameless spectacle they issued a public pastoral letter demanding the Grimkes stop such meetings at once. Even many abolitionist leaders were nervous: it was not then considered seemly, or civil, for women to speak in public at all; but if they were to speak, it should be only to other women. The grounds were both biblical and customary. (If this seems outlandish, it’s worth noting that some very prominent church groups — looking at YOU, Southern Baptists, and you, too, Francis— continue to enforce similar rules today.)

Yet while their meetings were advertised for women, men simply barged in, day after day, in droves; no one was able to stop them. But the complaints also continued. And soon, as one biographer put it,

[Angelina} had learned what it was to have halls refused because she was a woman, to see herself attacked in the public press, to know she was upbraided from many church pulpits, and to read and hear the epithets that were hurled at her person, much as they had been at the male abolitionists: “Sabbath-breaker,” “infidel,” “heretic,” “incendiary,” “insurrectionist,” “disunionist”; particularly for herself, “woman-preacher,” “female fanatic”; and for them all, “amalgamationist.”

She could comment dryly toward the end of the summer, “Since I have studied human rights & had my own invaded, ” the woman’s rights cause had become her own. The conception she then expressed remained with her ever after. She saw no conflict between her two great causes.

When she received a letter of reproof for mixing the issues of women speaking and abolition from two prominent abolitionists, poet John Greenleaf Whittier and organizer Theodore Weld, Angelina responded firmly:

“Can you not see the deep scheme ofthe clergy against us as lecturers?…[to] persuade the people it is a shame for us to speak in public, and that every time we open our mouths for the dumb we are breaking a divine command? . . . What then can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence?”

Under the feet, under the bus. The civility she challenged, first reluctantly then with gathering force, would have dictated silence. So, “what then?” Although not physically strong, the Grimkes saw their duty; the tour went on.

The following year, a crisis in civility gripped Philadelphia.

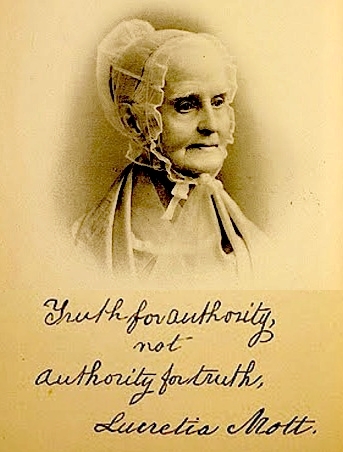

The Grimkes joined with another outspoken Quaker abolitionist, Lucretia Mott, and others in a project to remedy the fact that so many venues were closed to abolitionists: they would build their own, for meetings and conventions. And so they did, raising a large sum, and calling it Pennsylvania Hall. It opened on May 14, 1838, hosting a series of large meetings. Lucretia spoke several times, and Angelina Grimke was slated for a major address on the night of May 17.

She did speak, for an hour. But as she did so a proslavery mob gathered outside. They had been incited in part by widely-distributed flyers calling for “citizens who entertain a proper respect for the right of property,” to “interfere, forcibly if they must, and prevent the violation of these pledges (the preservation of the Constitution of the United States), heretofore held sacred.” And so they did.

As Grimke spoke, the mob threw bricks and other missiles through the windows, and soon set the building on fire. Mott and Grimke escaped unharmed; but by the following morning, Pennsylvania Hall had been burned to the ground. Its venture in civility had lasted three days. Ah, but was it sacrificed to the “Preserving of sacred pledges”?

Something else went up in smoke that week. On May 14, a few hours before Pennsylvania Hall officially opened, Angelina Grimke and Theodore Weld were married. Sarah was among a small group of guests.

By this action the sisters left Quakerism; deliberately, consciously. They had had enough of its Establishment-enforced silences. Theodore Weld was a non-Quaker. In those days such “marrying out” — and even Sarah’s mere presence thereat– were grounds for immediate disownment.

After her marriage, Angelina Grimke Weld retired to a private family life; sister Sarah stayed at her side as a companion/servant.

For Lucretia Mott, the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall did not dampen her devotion to pacifism or activism. She became the most well-known female public speaker in the country. Nevertheless, the following twenty years made her commitments increasingly difficult to keep.

By late 1860, when Abraham Lincoln, whom she scorned as a spineless compromiser on slavery, was about to win the presidency amid rising talk of secession, she found herself at a public meeting to remember John Brown. Brown, the prophesied abolitionist terrorist, had attacked a federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, hoping to use its store of weapons to spark and equip a slave insurrection across the South.

His raid had failed, and Brown was hung. But his vision of a national bloodbath that would wipe out slavery was about to begin playing out on another, much larger stage. And Lucretia insisted, not entirely convincingly to my ears, that her paying homage to his memory did not compromise her peace principles.

We did not countenance force, and it did not become those–Friends and others–who go to the polls to elect a commander-in-chief of the army and navy, whose business it would be to use that army and navy, if needed, to keep the slaves of the South in their chains, and secure to the masters the undisturbed enjoyment of their system

–it did not become such to find fault with us because we praise John Brown for his heroism.

For it is not John Brown the soldier that we praise; it is John Brown the moral hero; John Brown the noble confessor and martyr whom we honor, and whom we think it proper to honor in this day when men are carried away by the corrupt and pro-slavery clamor against him.

Our weapons were drawn only from the armory of Truth; they were those of faith and hope and love. They were those of moral indignation strongly expressed against wrong. Robert Purvis [1810-1898: a longtime black abolitionist, and friend of the Motts] has said that I was “the most belligerent non-resistant he ever saw.”

I accept the character he gives me; and I glory in it. I have no idea, because I am a non-resistant, of submitting tamely to injustice inflicted either on me or on the slave. I will oppose it with all the moral powers with which I am endowed. I am no advocate of passivity. Quakerism, as I understand it, does not mean quietism. The early Friends were agitators; disturbers of the peace; and were more obnoxious in their day to charges, which are now so freely made, than we are.”

Lucretia Mott, Remarks delivered at the 24th annual meeting of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, October 25-26, 1860

With that, Lucretia became in a real sense the obverse of the gentle, almost invisible Quaker reformer John Woolman.

Or maybe not the obverse; more like one pole of a dialectic, one that is ongoing among Quakers and other like-minded persons:

How is “civility” shaped (& misshapen) by other circumstances? And how and how much does its importance vary with changes in these circumstances? To what extent is it in the eye of the beholder? Does its violation lead to, or justify, violent responses?

And who, when push comes to shove, will be the judge?

The post Civility, Schmivility: A Quaker Dialectic, Then & Now appeared first on A Friendly Letter.

She could comment dryly toward the end of the summer, “Since I have studied human rights & had my own invaded, ” the woman’s rights cause had become her own. The conception she then expressed remained with her ever after. She saw no conflict between her two great causes.

She could comment dryly toward the end of the summer, “Since I have studied human rights & had my own invaded, ” the woman’s rights cause had become her own. The conception she then expressed remained with her ever after. She saw no conflict between her two great causes. I accept the character he gives me; and I glory in it. I have no idea, because I am a non-resistant, of submitting tamely to injustice inflicted either on me or on the slave. I will oppose it with all the moral powers with which I am endowed. I am no advocate of passivity. Quakerism, as I understand it, does not mean quietism. The early Friends were agitators; disturbers of the peace; and were more obnoxious in their day to charges, which are now so freely made, than we are.”

I accept the character he gives me; and I glory in it. I have no idea, because I am a non-resistant, of submitting tamely to injustice inflicted either on me or on the slave. I will oppose it with all the moral powers with which I am endowed. I am no advocate of passivity. Quakerism, as I understand it, does not mean quietism. The early Friends were agitators; disturbers of the peace; and were more obnoxious in their day to charges, which are now so freely made, than we are.”